How should we handle areas currently covered by FCC high cost programs in the context of the BEAD funding?

Analyzing the "Enhanced A-CAM" proposal by small rural providers

At this point, most observers know the letters in the broadband alphabet soup: RDOF, CAF, ARPA CPF, ARPA SLFRF, BIP, RUS, and of course BEAD. But how about a show of hands: who understands A-CAM and why it matters? Deep in the bowels of the FCC’s filing system there’s an important debate happening about the future of subsidies for rural broadband service in the context of other federal broadband programs. Rural ISPs are trying to lock-in long-term subsidies from the FCC in exchange for offering 100/20 broadband service and taking those locations off the board when the Infrastructure Bill funding is parceled out.

The Alternative Connect America Model (“A-CAM”) program is a monthly subsidy from the FCC’s Universal Service Fund that covers about 1.27 million Broadband Serviceable Locations. According the last Form 477 filing with data as of December 2021, about half — 54% — of the A-CAM areas are already served at 100/20 or better. Fifteen percent of the areas are Unserved, and 31% are Underserved. Put another way, A-CAM areas represent 190,000 of the 7.6 million Unserved locations that will be the focus of the BEAD program, and represent 394,000 Underserved locations out of 5.6 million Underserved nationally. The other 686,000 locations in A-CAM areas are already Served by 100/20 broadband.

A-CAM Broadband Coalition, the group of small rural ISPs, have a proposal in front of the FCC they would provide 100/20 Mbps broadband service to 98-100% of locations in their service area in exchange for 8-11 year extensions of their subsidies. Using one version of the proposal, it’s $1.44 billion per year in subsidy, an incremental $15.8 billion on top of what has already been committed.

This is directly related to the NTIA’s BEAD program because locations are ineligible for BEAD if they are covered by an “enforceable federal, state, or local commitment to deploy qualifying broadband.” It’s likely that if the FCC approves this A-CAM extension, these locations would not be eligible for BEAD funding.

A little bit of history. In early 2017, after a lengthy process, the FCC awarded 182 “rate-of-return” ISPs ten year’s worth of subsidies to provide 25/3 or 10/1 broadband service to 714,000 locations. Then, in 2019 — not that long ago — they added 363,000 locations as part of A-CAM II. The amounts, for both A-CAM I and A-CAM II, aren’t small:

The total amount of A-CAM [I] support and transition payments that these authorized carriers will receive over the course of the 10-year term is $5,283,553,352, averaging $528,355,335 on an annualized basis.

The A-CAM II support authorized totals $491,442,713.67 per year and $4,914,427,136.70 over the full 10-year term.

Now, six years later, the world looks different. DSL broadband at 25/3 or 10/1 are both ancient history. And the federal government has made it a priority to get every American 100/20 broadband service.

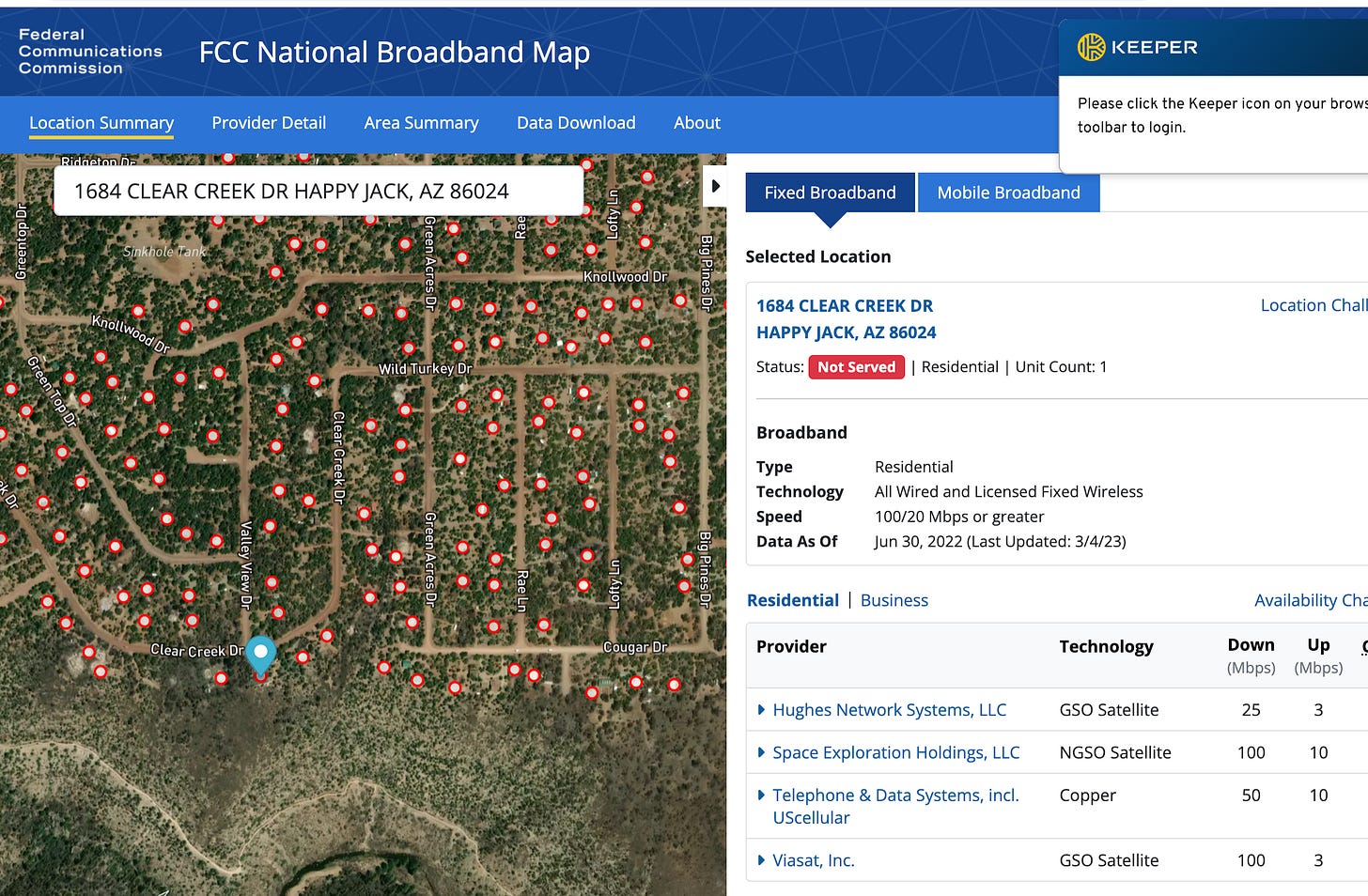

Before going any further, let’s look at some of the locations we’re talking about. First is the town of Happy Jack, Arizona, where we’re subsidizing Telephone and Data Systems’s 50/10 DSL.

Here’s another in Chatom, Alabama, where Millry Corporation is offering 25/3 DSL.

Here’s an example where the provider has built out a fiber-to-the-home network: Grand River Mutual Telephone serves the town of Clio, Iowa, and all of the surrounding area with symmetrical gigabit fiber. (It wouldn’t come up in the map as 100% served because there are make-believe locations that they didn’t claim to serve).

Here’s an example where the A-CAM company — Kaplan Telephone Company — is providing 30/5 licensed fixed wireless.

There’s an important distinction to keep in mind as we think about broadband buildout. An ISP considering entering a market has to think about both the capital expenditure of building the network and the ongoing operating expenses of running the network. A rural area will be more expensive to build a network because you need more wire to reach fewer people. Once the network exists, a similar argument can be made about operating costs. Maybe truck rolls are more expensive because the technicians can do fewer jobs per day. Maybe they are more prone to outages since there is more wire to maintain.

It’s unclear to me whether this A-CAM proposal is a capex program or an opex subsidy. If we provide money with a strict buildout requirement, it seems that’s funding capex. But we’re also providing money to locations that already have 100/20 service, so that functions as an opex subsidy.

It might be helpful to break down these locations into three categories:

Locations that already have fiber-to-the-home service.

Locations that are reasonable cost, but haven’t been upgraded (the fixed wireless example above, and the Arizona case would both fall into this category).

Locations that haven’t been upgraded because they are extremely high cost. Maybe the FTTH service serves the town but doesn’t reach to a mountainous area outside the town. Or maybe there’s no town at all.

For the first case, these locations have ~5.5 years left at their current subsidy level. When that expires, I think there should be a new look at the operating costs in running a rural network vs an urban network and decide from there what level of continued opex subsidies are required. Since they’re Served by future-proof broadband, they’re completely ineligible for BEAD grants.

In the second case, these locations should go into BEAD. The provider is getting a sizable subsidy but has continued to provide inadequate DSL or fixed wireless service. I see no reason why the existing provider should get keep those locations without any competition.

The third case is the hardest. First, let’s look at deployment timelines. Under the A-CAM Enhancement proposal, providers would offer 100/20 service to 50% of their locations by the end of 2026, reaching 100% by the end of 2031. Considering that these areas are already ~50% covered by 100/20 service, it’s reasonable to expect the new networks would be in the back half of that timeline — 2027 to 2031. According to NTIA, BEAD’s implementation will start in 2024 and last four years. It appears a BEAD-funded network would appear earlier, but there’s considerable uncertainty this far out and at an aggregated level.

Next, let’s try to imagine what would happen if these locations were in BEAD. Presumably if the incumbent ISP is planning to build fiber to them eventually with their A-CAM subsidy, they’d put in a grant proposal under BEAD. For a hard to reach location, they may be the only proposal. Or, there might be another proposal, which has the potential to bring down the cost. Neither of those seem like bad outcomes.

One of the arguments for the A-CAM proposal is that it increases the amount of money we’re throwing at the Digital Divide. If BEAD funding can’t close the Digital Divide, there’s a stronger case to use the FCC’s high-cost program to bring broadband to these locations. If BEAD can fund these locations, it’s a hard case to make to use FCC Universal Service money. Arguing there isn’t enough BEAD money, last fall the A-CAM Broadband Coalition published a study that estimated it will take between $397 billion and $478 billion to reach all the Underserved. That study is many multiples of my estimates of how much it will take to close the Digital Divide, and I tried to explain why I think the estimate is way, way too high.

But at the state level, things look different. While I estimate we can reach 76% of the Unserved and Underserved with BEAD funds, some states come up way short. In Nebraska, with an estimated average cost to pass a location of $15,621, they can only reach an estimated 24% of their Unserved and Underserved. Nebraska could be more than $1 billion short if they wanted to deliver fiber to everyone. (I’ve written about it before, but the Infrastructure Bill didn’t push enough money into high cost states. States with higher costs are at a serious disadvantage.) If a state will run out of money, and A-CAM can bring an enforceable commitment to deliver fiber-to-the-home, that’s a stronger case.

A-CAM funding comes from the FCC’s Universal Service Fund, which is itself at a critical moment. As many know, its funding comes from a surcharge on phone bills. But the “contribution base” — the number of phone lines — is shrinking. That means to generate the same amount of money, the percentage of the total phone bill needs to go up. That’s been happening quarter-over-quarter for years. A contentious FCC proceeding last year mostly showed that there are two sides, and they’re far apart: a vague “tax Big Tech ad revenue” camp and a “expand the base by adding a small surcharge to all broadband plans” camp. If neither of those seems like a fun solution, one way to kick the can down the road is to shrink the amount of money committed in Universal Service Fund programs. Extending A-CAM support does the opposite by committing $1.4 billion per year for 11 additional years, through 2039 in one of the proposals.

Where does all this leave us on the A-CAM proposal. Here are my recommendations:

Congress should amend the Infrastructure Bill to provide more funding to expensive states. The 10% of BEAD funds allocated based on high-cost locations doesn’t move enough money into states west of the Mississippi river where it can be 4 or 5x as expensive to bring fiber than it is in eastern states. Since that isn’t likely,

NTIA should do everything they can with the 10% high-cost allocation to make it more fair. Try to get all of that $4.25 billion into the high-cost states. It won’t be enough.

But, these A-CAM subsidies are not good policy. These areas should be subject to the same competition that BEAD will bring to other areas. Committing $1.4 billion a year in subsidies through 2039 out of a fund that’s on a shaky foundation is not responsible. The FCC should vote it down.

If a version of “Enahanced A-CAM” does go forward, my recommendation would be split A-CAM areas into three groups: (1) already-Served locations, (2) reasonable cost areas, and (3) extremely high cost areas. Then design an FCC program that looks much more like a capex program and fund the extremely high cost locations in states don’t have enough BEAD funding.

On a longer timeline, update our understanding of the difference in operating a rural network once the infrastructure is in place. Then design ongoing opex subsidies for rural networks based on that new understanding.

Mike, My concern regarding the Enhanced A-CAM program is the exact same problem I have with the "new" FCC National Broadband Map and the FCC mandated ISP Broadband Label and the BEAD funding provision on the requirement that ISPs receiving funding ensure device on the customers premises testing for Speed -Latency (BEAD NOFO program page 64 i. Speed and Latency)

Can you guess what it is? Wait for it, every data point reported/posted or measurement taken is done by the ISPs. This entire theater of the absurd continues the FCC/ISP (Carriers) preference (of course) for a NON-TRANSPARENT, NON INDEPENDENTLY VALIDATED DATA BASED BROADBAND MARKETPLACE ...Just like they have insisted on from the beginning of the E-RATE program which, wait for it, in NOT TRANSPARENT and everyone associated with the E-RATE "Reform" NOPR back in the day knew the program even then had about 40% waste fraud and abuse built in but as the FCC staffer stated time and time again they didn't have the manpower to go after this egregious situation so the whole "reform" exercise was a way to justify and increase on the tax/fees that supported the program with the extra funds coming in being discounted by at least 40%!

Consumers what a TRANSPARENT BROADBAND MARKETPLACE and they want to be able to TRUST THE ISPs DATA (a truly revolutionary concept)

Here is how we have defined the current broadband ecosystem at PAgCASA and how we have designed the State level solution.

We are not under any elusions at PAgCASA and realize only a few states will see the positive effects of empowering their constituents with a transparent broadband marketplace and data they can trust.

THE PROBLEM

• Broadband Data is unreliable

o ISP reported data on the New FCC National Broadband Map Inflates network speed and territory served.

o Consumer generated speed test data faces technical challenges and is largely unreliable as are crowdsourcing data analytics and alike.

• The Broadband Marketplace is not transparent, with all the power residing with the ISPs, not with consumers.

o The FCC has exercised little enforcement when it comes to consumer’s complaints and that will continue.

THE SOLUTION

• Leverage NTIA’s NOFO BEAD program- i. Speed and Latency (page 64, language below) to begin to build out a statewide, independent third-party run broadband monitoring/metering program where:

o ISPs pay an independent third party (PAgCASA) to lease edge cyber secure industry standard network monitoring devices (the same ones used by Verizon/AT&T/Comcast) as mandated by the BEAD funding requirements, with PAgCASA , not the ISP, monitoring the edge secure data.

• Have your State, not the ISPs, oversee an independent, third-party data validation process to ensure the information on the new FCC mandated ISP Broadband Labels, designed to give much needed information about network performance and pricing to consumers, is accurate. Have the ISPs share the cost associated with this information validation program designed to protect consumers.

THE COST

If your State follows the formula outlined above the ISPs in your State will be responsible for underwriting the expenses associated with your State having the most up to date and accurate broadband State map and the best consumer empowering Broadband Marketplace.

Your State Needs a Broadband Sheriff to Enforce the Authority NTIA and the FCC have Already Put in Your hands, and to make the ISPs pick up the Tab!

The entire broadband network ecosystem is defined by two distinct data sets both of which are unreliable.

ISPs, with the implicit consent of their regulatory agency, the FCC, have for several decades been able to inflate their network service speeds (Advertised/Marketing Network Speed), quality of service and service territory (FCC’s Ten Day Rule). The Old FCC Broadband Map was roundly criticized for its inaccurate data as is the New FCC Broadband Map.

Technical problems associated with customer generated speed testing data is well known, and its flaws well documented.

Your State has been given the authority it needs to police your ISPs (see NTIA NOFO paragraph below) and FCC’s New Broadband Labeling Requirement (see below) leaves it up to the States to validate/ensure the accuracy of the new ISPs labeling information!

PAgCASA’s Statewide Broadband Sheriff initiative has the industry standard monitoring/metering devices and edge cybersecurity for data protection needed to launch a statewide “trust but verify” initiative with the ISPs picking up the cost of leasing the devices while PAgCASA monitors the device, stores the data in a SOC and works with the State or the State’s Broadband Mapping partner to display the validated data.

NTIA NOTICE OF FUNDING OPPORTUNITY BROADBAND EQUITY, ACCESS, AND DEPLOYMENT PROGRAM EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

i. Speed and Latency

To ensure that Funded Networks meet current and future use cases and to promote consistency across federal agencies, NTIA adopts the compliance standards and testing protocols for speed and latency established and used by the Commission in multiple contexts, including the Connect America Fund and the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund.78 In order to demonstrate continued compliance with these standards, subgrantees must perform speed and latency tests from the customer premises of an active subscriber to a remote test server at an end-point consistent with the requirements for a Commission-designated IXP.79

https://www.fcc.gov/broadbandlabels