There are [still] too many locations in the National Broadband Map

For many months, states have raced to add locations to the FCC’s National Broadband Map, trying to maximize their allocation of broadband funding from the Infrastructure Bill. But in a few short weeks, the NTIA will allocate funding and then my prediction is we’ll never hear about “missing locations” again. Instead, we’ll focus on the opposite problem: there are too many locations in the National Broadband Map.

This isn’t new; I wrote about this in January and things haven’t changed much. Overall there are 113.3 million Broadband Serviceable Locations according to the Broadband Service Location Fabric which underpins the Broadband Map. Because one “location” can represent more than housing unit, such as in the case of an apartment building, there are 158.4 million “units” according to the Fabric (BSLs explicitly include businesses, so the Fabric “units” is both housing units and business locations). The Census, which also tracks the number of housing units in the country, reports there are 140.5 million housing units. Some difference is to be expected given the inclusion of businesses in the Fabric, but a difference of almost 18 million suggest something else could be going on.

As we can see in the table above, the Fabric actually has extra locations in rural areas as compared to more dense counties. In the least dense 2,148 counties in the U.S. there are 30.1 million housing and business units and 24.6 million according to the Census — the Fabric has 22% more. Whereas in the most dense 996 counties, the Fabric only has 10% more. In the chart below, the counties are ordered from the most dense on the left to the least dense on the right. As the counties get more rural, the Fabric reports an increasingly higher number of locations relative to the Census. In many rural counties, it’s routine to have 40% more locations in the Fabric than the Census.

Texas has the most of these locations, in real terms and as a percentage of rural locations. In the least dense 206 counties in Texas, there are 2.44 million “units” according to the Fabric, and only 1.81 million according to the Census, a difference of 637,000 locations. Real County, Texas, for example, has 3,737 housing and business units according to the Fabric, but only 1,656 housing units according to the Census — 126% more in the Fabric. That seems like a good place to start.

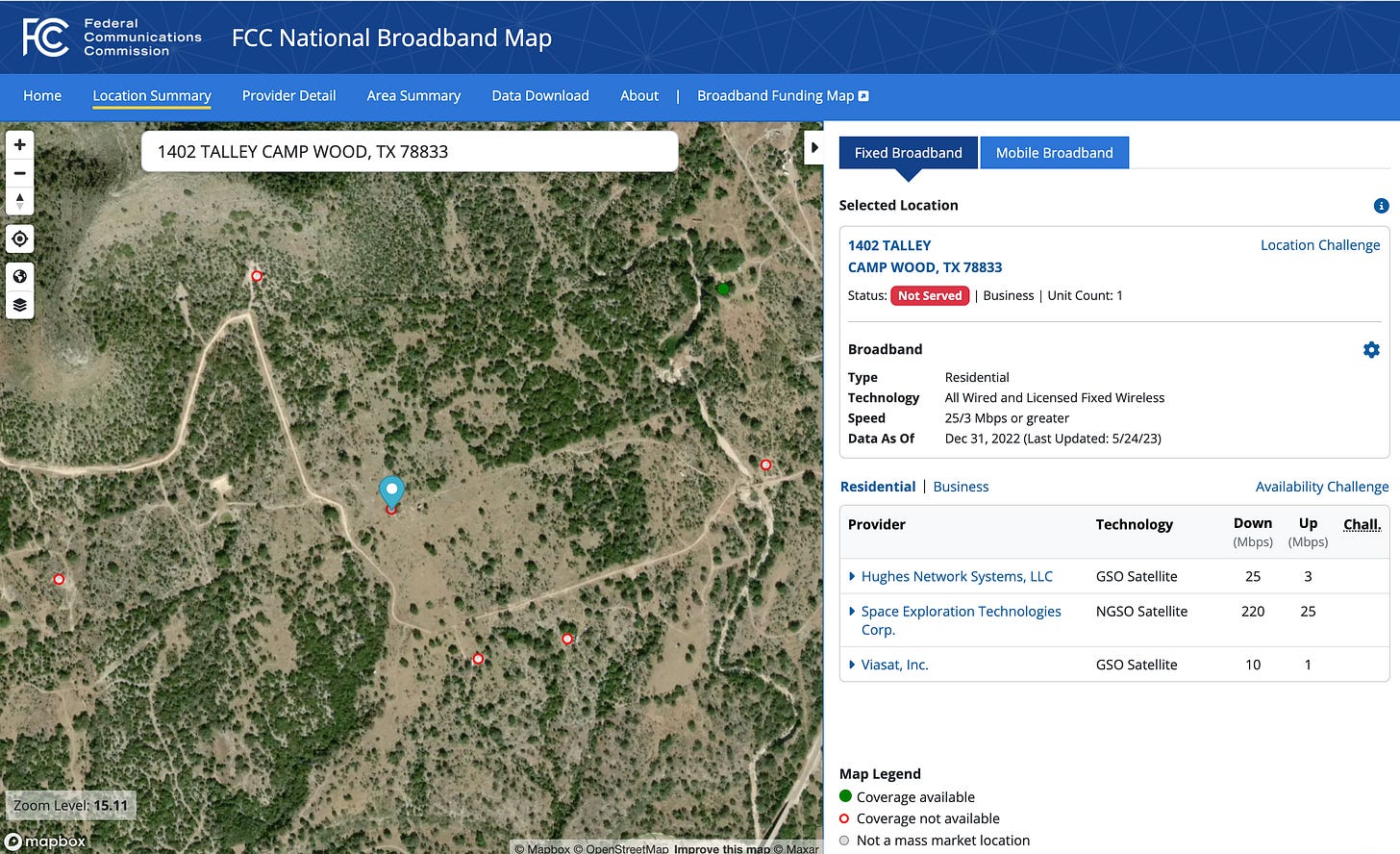

It’s not difficult to find these locations — you can just scroll into the map in any rural area in basically any state. But the Fabric provides an even easier way to identify them using the confidence codes of the locations. The Fabric has an address confidence code and a land use code. When the location has the lowest confidence code and a land use of agriculture, they’re very likely to be questionably real at best. The below locations are from Camp Wood, Texas, in Real County.

From my short investigations into some of them, it appears what often happens is the land has been parceled out. It has a private owner. So Cost Quest’s software, which is trying to identify locations, works very hard to find a structure on the parcel, sometimes identifying a bush or nothing at all, and sometimes identifying some type of human-made structure but certainly not a house (or a business). These locations (generally) are given an address by the Fabric, but you can’t find the addresses anywhere in Google, and it’s extremely unlikely they’d be in a 911 database.

While there are a lot of locations where nothing at all exists, some do have something on them. Sometimes it looks like a house. Some of the questionable ones seem to be remote hunting ranches. Some of these ranches have electricity.

The broadband Fabric is an estimate. It’s a model. It uses the available data — parcels satellite imagery, tax records, etc — and makes a guess at where a “Broadband Serviceable Location” exists based on that data. Some error, both leaving out some locations and including too many, is expected. This is particularly true since the definition of a “Broadband Serviceable Location” is itself squishy. The FCC says:

As an important first step, we adopt as the fundamental definition of a “location” for purposes of the Fabric: a business or residential location in the United States at which fixed broadband Internet access service is, or can be, installed.

It goes on to define a non-residential BSL:

We will treat the following as business locations in the Fabric: all non-residential (business, government, non-profit, etc.) structures that are on a property without residential locations and that would be expected to demand broadband Internet access service.

The FCC doesn’t, and couldn’t, define every type of location in the country and whether it could demand broadband service. This is an issue that Cost Quest told Congress about while Congress considered the Broadband DATA Act which created the Fabric, and I wrote about it for Slate in April 2021.

We haven’t heard much about locations that aren’t real and thus don’t need broadband service. States don’t have an incentive to clean up this part of the map at this time because it could very directly decrease their allocation. My prediction is after the allocation of money is done, that will change.

Mike, this is tremendous work.

One question: when you say you don't think we'll hear about missing locations once the state allocations happen — what about when states go to make subgrants? My understanding was that they're still bound to allocating funds based on the number/proportion of unserved BSLs in a project area. If that's true, it seems like the CQA fabric (and the completeness of it) stay relevant, but would love to know if there's a different or more definitive answer on that.

Hi Mike,

Thanks for this invaluable work. In your "Allocations and BDC Numbers" work sheet, what is the method (and reasoning) behind calculating the "best available" stats?

Thanks,

John